Saturday, May 30, 2009

Thursday, May 28, 2009

Build Your Dreams. Blow Your Mind

"I didn't really convinced him. The facts convinced him. What -- has already done is ridiculously difficult to do. And they've done it anyway." --- Charlie Munger

Tracking BYD:

China's Top 10 PC by Model in 2007

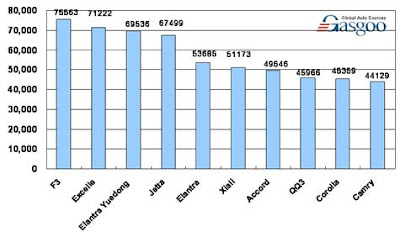

Top 10 Sedan Brand's Line-up by Sales Jan-Dec08

Top 10 Sedan Brand's Line-up by Sales Jan-Apr09 (very impressive)

Sales of BYD Auto in April 2009 (by model)

PV OEMs Market Share 2008PV OEMs Market Share Change 2008 vs 2007

BYD E6 Pure Electric Vehicle

BYD Dual Mode Electric Vehicles

Related Articles:

Shenzhen to subsidize buyer of BYD hybrid car

Only 'green' vehicles permitted to enter Beijing

Warren Buffett's Big Battery Play

What business is BYD really in?

More on BYD and Wang ChuanFu

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

Warren Buffet's Big Battery Play

David Sokol, the chairman of an Iowa-based utility holding company called MidAmerican Energy Holdings, which is 80 percent owned by Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway, has for the most part been quieter. But Sokol and MidAmerican Energy have been positioning their business for a low-carbon future. MidAmerican's investments in wind power mean that it generates more power from renewable source than any other regulated utility, as best as I can tell. It was Sokol, at Buffett's request, who engineered MidAmerican's investment in BYD, the Chinese battery-maker and auto company that is building low-cost electric cars. (See Warren Buffett Takes Charge, my story about BYD that ran last month in FORTUNE.) And now there's more news from MidAmerican, and you heard it here first: The company will soon begin testing batteries from BYD that, if all goes well, could store electricity on a large scale at a reasonable cost.

That's a big deal.

Just a few details: This fall, MidAmerican will build a 2 megawatt storage facility using BYD batteries at an existing substation in Portland, Oregon, where it operates the local utility, Pacific Power. BYD, meanwhile, is building a bigger storage facility in China, and plans to build a third one in a still-undisclosed location on in southern California. That's about all I can tell you because BYD is reluctant to talk about its research.

The 2 megawatts of battery storage in Portland will allow MidAmerican to test BYD batteries to see how well they charge, what control systems are needed to discharge the electricity and to analyze their reliability and cost. "It will let us do a fair amount of testing to understand the economics of a 100 or 200 megawatt storage facility to back up wind," Sokol says.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Secret of Googlenomics: Data-Fueled Recipe Brews Profitability

Google depends on economic principles to hone what has become the search engine of choice for more than 60 percent of all Internet surfers, and the company uses auction theory to grease the skids of its own operations. All these calculations require an army of math geeks, algorithms of Ramanujanian complexity, and a sales force more comfortable with whiteboard markers than fairway irons.

Varian, an upbeat, avuncular presence at the Googleplex in Mountain View, California, serves as the Adam Smith of the new discipline of Googlenomics. His job is to provide a theoretical framework for Google's business practices while leading a team of quants to enforce bottom-line discipline, reining in the more propellerhead propensities of the company's dominant engineering culture.

Googlenomics actually comes in two flavors: macro and micro. The macroeconomic side involves some of the company's seemingly altruistic behavior, which often baffles observers. Why does Google give away products like its browser, its apps, and the Android operating system for mobile phones? Anything that increases Internet use ultimately enriches Google, Varian says. And since using the Web without using Google is like dining at In-N-Out without ordering a hamburger, more eyeballs on the Web lead inexorably to more ad sales for Google.

The microeconomics of Google is more complicated. Selling ads doesn't generate only profits; it also generates torrents of data about users' tastes and habits, data that Google then sifts and processes in order to predict future consumer behavior, find ways to improve its products, and sell more ads. This is the heart and soul of Googlenomics. It's a system of constant self-analysis: a data-fueled feedback loop that defines not only Google's future but the future of anyone who does business online.

What Are the Odds?

I don’t think complex situations like this one can be predicted. There are too many uncontrollable or unmeasurable factors. Afterwards, of course, it will appear that some people had gotten it just right: since there are many people making many predictions, no doubt some of them will get it right, if only by chance. But that doesn’t mean that, if not for some unforeseen random turn, things wouldn’t have gone the other way.

The social historian (and socialist) Richard Henry Tawney, wrote, “Historians give an appearance of inevitability… by dragging into prominence the forces which have triumphed and thrusting into the background those which they have swallowed up.” And the (neo)conservative historian Albert Wohlstetter said it this way: “After the event, of course, a signal is always crystal clear. We can now see what event the disaster was signaling … but before the event it is obscure and pregnant with conflicting meanings.”

In some sense this idea is encapsulated in the cliché that “hindsight is always 20/20,” but people often behave as if the adage weren’t true. In government, for example, a “should-have-known-it” blame game is played after every tragedy. In the case of Pearl Harbor, for example, seven committees of the United States Congress delved into discovering why the American military had missed all the “signs” of a coming attack. One of the pieces of evidence cited as a harbinger recklessly ignored by the U.S. Navy was a request, intercepted and sent to the Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington, that a Japanese agent in Honolulu divide Pearl Harbor into five areas and make future reports on ships in harbor with reference to those areas. Of special interest were battleships, destroyers and carriers, as well as information regarding the anchoring of more than one ship at a single dock. In hindsight , that sounds ominous, but at other times similar requests had gone to Japanese agents in Panama, Vancouver, Portland and San Francisco. [The analysis is most famously laid out in the 1963 book, “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision,” by Roberta Wohlstetter, who was married to Albert, noted above.]

In addition to the intelligence reports that in hindsight seem to point toward a specific attack, there is also a huge background of useless intelligence, each week bringing new reams of sometimes alarming or mysterious messages and transcripts that would later prove misleading or insignificant. In advance of the event, you can’t tell one sort from the other.

It is hard to say whether people are too optimistic or too pessimistic. That depends on the person. But we should keep in mind that it is easy to concoct stories explaining the past, or to become confident about dubious scenarios of the future. We should view both explanations and prophecies with skepticism.Can a full understanding of the probability of certain outcomes help reduce anxiety? For instance: would knowing the statistical frequency (or infrequency) of plane crashes help someone overcome a fear of flying? Would a smoker knowing the actual odds that he will get cancer make him less fearful of that outcome? In short, do we worry too much, or too little?

My mother worries too much. Some say I worry too little. I guess that shows a) that one cannot say “we” worry too much or too little, and b) that whether an individual worries too much or too little is not 100 percent inherited from your mother.

I was once on a plane that experienced so much turbulence that when I looked out the window, the wings seemed to flap up and down like a bird’s. I noticed, also, that the woman in the window seat next to me looked pale and terrified. Personally, I took comfort in knowing how many miles planes fly through heavy turbulence without any problems at all. So I explained to the woman how planes were designed to withstand such conditions, and told her the slim odds of anything bad happening. When I finished, she turned away and reached for the barf bag.

Some people take solace in an understanding of their environment, others don’t. For me, an understanding of the role played by chance has taught me that one important factor in success is under our control: the number of at-bats, the number of chances taken, the number of opportunities seized. As someone who has taken risks in life I find it a comfort to know that even a coin weighted toward failure will sometimes land on success. Or, as I.B.M. pioneer Thomas Watson said, “If you want to succeed, double your failure rate.”Wednesday, May 13, 2009

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

Saturday, May 9, 2009

Wednesday, May 6, 2009

Tuesday, May 5, 2009

Saturday, May 2, 2009

One on One with Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman Berkshire Hathaway

GHARIB: How are Berkshire's businesses doing so far this year?

MUNGER: Mixed. But the two biggest businesses, which are insurance and utilities, are flourishing. So I would say that even with all of the bad effects we've had, we're not catching our full share of the horror.

GHARIB: Some of Berkshire's investments are in financial stocks like American Express and Wells Fargo. Does it make sense to continue to hold on to these stocks? What's your outlook for the financials?

MUNGER: Well, I think the companies which we are invested have very respectable futures from this point forward. The financial world should be restructured so that these people who are too big to fail are not allowed to behave in such a gamey fashion. I'm pessimistic with the regulatory changes that come down. I'm afraid they won't be as severe as we need.

GHARIB: As an investment, investors should stay away from financials for now?

MUNGER: I didn't say that. We need the financials. We can't have a modern civilization without strong financial companies. But we don't need them as swashbuckling and as crazy and as venal as they've been.

GHARIB: Now I understand there are three candidates who are being considered to take over from Warren Buffett when the time comes. I know you're not going to tell me who they are. But what do you think is the most important characteristic for this job?

MUNGER: I don't think there's any one way that's the right way to run a corporation. Different people have different styles. Different people have different strengths. I am quite confident that Berkshire will be governed very well long after Warren and I are gone.

Thanks to Sanjeev Parsad from Corner of Berkshire and Fairfax for the original reference

Other Related Articles

Here's the Story on Berkshire's Munger

Buffett's Partner Charlie Munger Blames Banks' "Evil and Folly" For Economic Crisis