Monday, December 21, 2009

Among the Last Skeptics Standing

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Friday, September 11, 2009

Buffett praises Trands' 30 great years

"I have to tell you that I now have nine suits made in China. I threw away the rest of my suits. Our director, my partner Charlie Munger, Walter Scott, and even Bill Gates now is wearing suits made by Dayang Trands. They know and love Madam Li for what she has accomplished.

"The suits we received that's made in china; we never had it altered a quarter of inch and they fit perfectly. Since I wear Madam Li's suits, I get compliments on it all the time. Maybe, Bill Gates and I should start a clothing store and sell the suit made by Dayang Trands. We will be great sales man, because we love them so much. Someday we might be even richer. Who knows?

Note: Thanks to Sanjeev from Corner of BRK and FFH for the original reference

Sunday, August 23, 2009

A conversation with theoretical physicist and mathematician Freeman Dyson

CHARLIE ROSE: So the world is getting warmer.

FREEMAN DYSON: No, I went to Greenland myself, where

the warming is most extreme. And it’s quite spectacular,

of course, what you see in Greenland.

CHARLIE ROSE: OK, but do you believe that if in fact

there continues to be global warming in those regions,

that we will eliminate the ice and, therefore there will

be a rising of the water level, and, therefore, at some

point it will threaten us all?

FREEMAN DYSON: No. I don’t believe that. I mean, the

point is that the sea level has been rising for 12,000

years. And it has nothing to do with global warming.

CHARLIE ROSE: Nothing?

FREEMAN DYSON: It’s a separate problem. I mean.

CHARLIE ROSE: But does global warming contribute to it?

FREEMAN DYSON: Probably. But we don’t know how much.

And it’s certainly not -- the main problem when you’re

dealing with a rising ocean -- I mean, we know it’s been

going on for 12,000 years. We know it has very little

to do with human activities. So it will be a great --

it will be a terrible mistake to think you solved the

problem of the rising ocean when you’re only dealing with

climate.

CHARLIE ROSE: OK, so is global warming bad?

FREEMAN DYSON: No, I would say warming is certainly real,

but it’s mostly happening in cold places at high latitudes,

and it’s also happening more in winter than in summer, and

it’s also happening more at night than in daytime.

CHARLIE ROSE: But is the emission of so much CO2 into the

atmosphere a good thing?

FREEMAN DYSON: Yes.

CHARLIE ROSE: Even though it breaks -- whatever it does

up there?

FREEMAN DYSON: Yes, I would say it’s a very good thing.

It makes plants grow better.

CHARLIE ROSE: So all the CO2 doesn’t bother you, even

though.

FREEMAN DYSON: No, that’s a big plus. And then against

that, you have possible harmful effects of warming. But

I think it is most important that warming is happening in

places that are cold. It’s happening in places where’s

it’s winter rather than in summer, and at night rather

than in daytime. So it means that it’s essentially

evening out the climate rather than just making everything

hotter.

CHARLIE ROSE: What’s interesting is that you are not

arguing with the facts. You are arguing with the

conclusions.

FREEMAN DYSON: Yes.

CHARLIE ROSE: What concerns you today? What do you worry

about?

FREEMAN DYSON: I worry about nuclear weapons.

CHARLIE ROSE: Yeah. There is this idea that physics has

had its century, that was the 20th century, and the 21st

century belongs to molecular biology and brain science.

FREEMAN DYSON: I think that’s quite likely to be true.

I mean, that -- it’s certain that physics has slowed down

during my lifetime, largely just because the experiments

have become so slow. But biology, at the same time, has

been speeding up. So, I think it’s probably true that

this century is the century of biology.

CHARLIE ROSE: What did you determine about the origins

of life?

FREEMAN DYSON: Well, I’m simply speculating that it

actually had two origins.

FREEMAN DYSON: That we had -- our living creatures are

made of two components, which is sort of hardware and

software, like computers. And the hardware being.

CHARLIE ROSE: Wait, living creatures are made of two

components, hardware and software?

FREEMAN DYSON: Yes. The hardware being sort of the

chemistry of things, what they call metabolism, the

eating and drinking and processing chemicals. All the

real processing, all the active things like nerves and

muscles and so on are made of hardware, proteins. And

then there is the software, which is the genes, the

genomes, and which is just the instructions for how to

build it.

And so we have these two components, which are very

separate in life, as we know it. So I’m making the

hypothesis that really, it was unlikely that they both

were there from the beginning. It’s much more likely

that they originated separately. So that…

CHARLIE ROSE: Simultaneously or…

FREEMAN DYSON: No, on the contrary. You had the

hardware first, and then you had life evolving without

genes for a long time. And then genes were then an

independent creature, which originally were parasites,

and then took over the direction, so they became then

-- became then a symbiosis, a collaborative system,

which both of them worked together. That seems to me

a reasonable point of view, but I don’t claim it’s true.

CHARLIE ROSE: Are you optimistic about all of us?

FREEMAN DYSON: Yes.

CHARLIE ROSE: In the end?

FREEMAN DYSON: Oh, very optimistic. It’s quite

amazing how much we’ve been able to do in the short

time we came down from the trees. We have talents,

which to me are quite extraordinary, because they

don’t have any obvious survival value. Like for

example, calculating numbers. I mean, who needs to

calculate numbers in order to survive? It’s not at

all clear. Why should we be able to compose string

quartets? Why should we be able to paint paintings?

Everything we do is so much more than you require

just to survive.

CHARLIE ROSE: Have we been kind to the planet?

FREEMAN DYSON: Yes. I would say on the whole, yes.

CHARLIE ROSE: Whom you look a bit like (ph).

FREEMAN DYSON: No, the fact is of course, we’ve done

a lot of damage to the planet, but we also repair the

damage. I grew up in England, and England was far more

filthy then than it is now. Because we had the

industrial revolution first. So England was much more

polluted than the United States ever has been, and

England now is quite comparatively clean. You can go

to London and your collar doesn’t get blacked in one

day.

CHARLIE ROSE: Have you been to Beijing?

FREEMAN DYSON: Yes.

CHARLIE ROSE: And you’re not bothered by that? And you

want them to build every coal-burning plant they want to

build?

FREEMAN DYSON: Yes. They should clean up the coal, but

of course that you can do. The global warming people

don’t make a distinction between carbon dioxide, which is

essentially, in my view, harmless, and the other things

in coal which are horrible -- soot and smog and nitrogen

oxide and all that stuff. There’s a lot of very ugly

stuff in coal, which you can get rid of by scrubbing the

coal and scrubbing the gases that come out of the fire

station. And so, the Chinese certainly can do a lot more

of that, and they are doing a lot more of that.

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

The Greenback Effect

IN nature, every action has consequences, a phenomenon called the butterfly effect. These consequences, moreover, are not necessarily proportional. For example, doubling the carbon dioxide we belch into the atmosphere may far more than double the subsequent problems for society. Realizing this, the world properly worries about greenhouse emissions.

The butterfly effect reaches into the financial world as well. Here, the United States is spewing a potentially damaging substance into our economy — greenback emissions.

To be sure, we’ve been doing this for a reason I resoundingly applaud. Last fall, our financial system stood on the brink of a collapse that threatened a depression. The crisis required our government to display wisdom, courage and decisiveness. Fortunately, the Federal Reserve and key economic officials in both the Bush and Obama administrations responded more than ably to the need.

They made mistakes, of course. How could it have been otherwise when supposedly indestructible pillars of our economic structure were tumbling all around them? A meltdown, though, was avoided, with a gusher of federal money playing an essential role in the rescue.

The United States economy is now out of the emergency room and appears to be on a slow path to recovery. But enormous dosages of monetary medicine continue to be administered and, before long, we will need to deal with their side effects. For now, most of those effects are invisible and could indeed remain latent for a long time. Still, their threat may be as ominous as that posed by the financial crisis itself.Tuesday, August 18, 2009

Recent Updates: BYD

Shanghai Automotive Industry Corp. (SAIC), one of China's leading automakers, reached accord with BYD Corp., a well-known battery supplier, to purchase the latter's lithium battery stacks, said sources. These battery stacks will be installed on hybrid models under Roewe, a proprietary brand of the automaker, they added. A sales executive with BYD confirmed that his company really signed an agreement with a domestic giant, but declined to tell its name.

Subsidy will help plug-in hybrid sales, BYD says

Chinese battery and vehicle maker BYD Co said it was bullish about sales of its F3DM plug-in hybrid car, after regulators recommended the energy-efficient model as eligible for government subsidies.

China's Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) recently unveiled the list of a first batch of new-energy vehicle models that have got regulatory approval for production and sale.

According to a statement on the MIIT website, there were five new-energy vehicle models in the list - Nanjing Iveco's electric commercial vehicle, Jianghuai Auto's electric engineering vehicle, JMC's electric service vehicle, Zotye Auto's electric light minibus, and BYD's plug-in hybrid sedan.

"Being the only sedan on the list, we qualify for the highest subsidy level of as much as 50,000 yuan ($7316) per unit. Hence, we are optimistic about the F3DM model's sales to individual customers, which will start next month," said a BYD spokesperson.

The compiler of Hong Kong's stock indexes said Friday it will make no changes to the constituents of the blue-chip Hang Seng Index but added Chinese battery and electric car maker BYD Co. [s:hk:1211] to the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index, or H-share index, lifting the number of constituents in the share tracker to 44.

Another company Buffett recently invested in is BYD, the Chinese battery giant that has released an electric vehicle with a range of 250 miles. Reiten met with BYD executives while in China with Gov. Ted Kulongoski on a trade mission, and those discussions have led to a compelling new collaboration Reiten calls "potentially a game- changer," with super-efficient batteries storing the extra electricity while the wind is humming or the sun is beating down, to transmit it through the system at a later time when it is needed. "BYD is the No. 1 cell phone battery manufacturing company in the world," says Reiten. "They have staked their company on being the best in terms of batteries and we think there are utility applications." The partnership could develop into something exciting. Then again, it could flop. Either way, there will be no quick fix to the challenges Reiten and PacifiCorp face. As he lays out his strategy Reiten has a lot to say about a lot of things, but he doesn't say much about coal, which is PacifiCorp's greatest asset and its greatest liability.

Sunday, August 16, 2009

Law of easy money

“IF FIVE hundred millions of paper had been of such advantage, five hundred millions additional would be of still greater advantage.” So Charles Mackay, author of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, described the “quantitative easing” tactics of the French regent and his economic adviser, John Law, at the time of the Mississippi bubble in the early 18th century. The Mississippi scheme was a precursor of modern attempts to reflate the economy with unorthodox monetary policies. It is hard not to be struck by parallels with recent events.

...

...

When the scheme faltered Law resorted to a number of rescue packages, many of which have their echoes 300 years later. One was for the bank to guarantee to buy shares in the Mississippi company at a set price (think of the various government asset-purchase schemes today). Then the company took over the bank (a rescue along the lines of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac). Finally there were restrictions on the amount of gold and silver that could be owned (something America tried in the 1930s).

All these rules failed and the scheme collapsed. Law was exiled and died in poverty. The French state’s finances stayed weak, helping trigger the 1789 revolution. The idea of a “fiat” currency was perceived to be the essence of recklessness for another two centuries and the link between money and gold was not fully abandoned until the 1970s, when the Bretton Woods system expired.

Of course, the parallels with today are not exact. Law’s system took just four years to collapse; today’s fiat money regime has been running for nearly 40 years. The growth in money supply has been less excessive this time. Technological change and the entry of China into the world economy have generated growth rates beyond the dreams of 18th-century man. But one lesson from Law’s sorry tale endures: attempts to maintain asset prices above their fundamental value are eventually doomed to failure.

Friday, August 14, 2009

Shai Agassi, Israel's Homegrown Electric Car Pioneer: On the Road to Oil Independence

and car industry of the future? And how can they get involved with Better Place?

Agassi: First thing they have to remember is that their first car will be electric. The young

generation today understands that ... we don't have enough oil in the ground and we don't have enough of an atmosphere to sustain them until they die if we don't switch early. And the earlier we switch ... the easier it is going to be to recover from what we -- our generation and the generations of the past -- have done to this planet, and the abuse that we've [inflicted on] natural resources .... And so the first thing to remember is your future is electric.

The second thing is that this is one of the most exciting times in this industry. We will have a billion electric cars on the road sometime around 2025 because we will have a billion people [driving] and there's no way they can be [driving] gasoline cars. Between now and 2025, a billion new cars need to be added and there will not be any industry that will be more exciting than this one. If you think of an industry that will make a billion of something, [with an average price of] $20,000, you're looking at a $20 trillion industry rising up from nothing today within the span of 10 to 15 years.

Those are the kinds of [things] that made Silicon Valley a great place to work and made biotechnology a great place to work and made the Internet such a fun place to be part of in 1995. If they're looking for something that will be the next big industry, there's no doubt in my mind that the electric car is the next big thing and that $20 trillion is just the core of this industry. There'll be batteries and services, innovation and new product technology. Everything will be reinvented and they've got to think of a way to get into this industry while they can.

Monday, August 3, 2009

Buffett says he sees America in Des Moines store

"We're not too good at avoiding challenges, but we're marvelous at surmounting them," Buffett said. Looking around the store, he added, "I don't see how anyone can be a pessimist about the future of the country."

Responding to questions from the audience, Buffett later said he thought President Barack Obama has "done a first-class job," as has U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner and others.

Other snippets included:

- On pollution controls contained in federal energy legislation: "We led the world into this, and we should lead the world out of it."

- On an oversupply of housing that's led to low prices: "Most of the problems in the housing market will be over in 18 months or something like that."

- On a mounting federal debt: "It is not dangerous where we are now. It may be dangerous where we are going."

- On taxes: "I would make the tax rates a little more progressive. I would help my cleaning lady and take a little more out of me."

Tuesday, July 28, 2009

Sunday, July 26, 2009

Saturday, July 25, 2009

Friday, July 10, 2009

Thursday, July 9, 2009

Tuesday, June 30, 2009

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Thursday, June 11, 2009

Tuesday, June 2, 2009

Fireside Chat -- Deflation … or Reflation?

Saturday, May 30, 2009

Thursday, May 28, 2009

Build Your Dreams. Blow Your Mind

"I didn't really convinced him. The facts convinced him. What -- has already done is ridiculously difficult to do. And they've done it anyway." --- Charlie Munger

Tracking BYD:

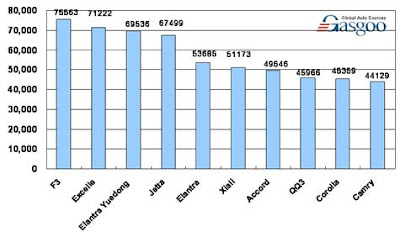

China's Top 10 PC by Model in 2007

Top 10 Sedan Brand's Line-up by Sales Jan-Dec08

Top 10 Sedan Brand's Line-up by Sales Jan-Apr09 (very impressive)

Sales of BYD Auto in April 2009 (by model)

PV OEMs Market Share 2008PV OEMs Market Share Change 2008 vs 2007

BYD E6 Pure Electric Vehicle

BYD Dual Mode Electric Vehicles

Related Articles:

Shenzhen to subsidize buyer of BYD hybrid car

Only 'green' vehicles permitted to enter Beijing

Warren Buffett's Big Battery Play

What business is BYD really in?

More on BYD and Wang ChuanFu

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

Warren Buffet's Big Battery Play

David Sokol, the chairman of an Iowa-based utility holding company called MidAmerican Energy Holdings, which is 80 percent owned by Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway, has for the most part been quieter. But Sokol and MidAmerican Energy have been positioning their business for a low-carbon future. MidAmerican's investments in wind power mean that it generates more power from renewable source than any other regulated utility, as best as I can tell. It was Sokol, at Buffett's request, who engineered MidAmerican's investment in BYD, the Chinese battery-maker and auto company that is building low-cost electric cars. (See Warren Buffett Takes Charge, my story about BYD that ran last month in FORTUNE.) And now there's more news from MidAmerican, and you heard it here first: The company will soon begin testing batteries from BYD that, if all goes well, could store electricity on a large scale at a reasonable cost.

That's a big deal.

Just a few details: This fall, MidAmerican will build a 2 megawatt storage facility using BYD batteries at an existing substation in Portland, Oregon, where it operates the local utility, Pacific Power. BYD, meanwhile, is building a bigger storage facility in China, and plans to build a third one in a still-undisclosed location on in southern California. That's about all I can tell you because BYD is reluctant to talk about its research.

The 2 megawatts of battery storage in Portland will allow MidAmerican to test BYD batteries to see how well they charge, what control systems are needed to discharge the electricity and to analyze their reliability and cost. "It will let us do a fair amount of testing to understand the economics of a 100 or 200 megawatt storage facility to back up wind," Sokol says.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Secret of Googlenomics: Data-Fueled Recipe Brews Profitability

Google depends on economic principles to hone what has become the search engine of choice for more than 60 percent of all Internet surfers, and the company uses auction theory to grease the skids of its own operations. All these calculations require an army of math geeks, algorithms of Ramanujanian complexity, and a sales force more comfortable with whiteboard markers than fairway irons.

Varian, an upbeat, avuncular presence at the Googleplex in Mountain View, California, serves as the Adam Smith of the new discipline of Googlenomics. His job is to provide a theoretical framework for Google's business practices while leading a team of quants to enforce bottom-line discipline, reining in the more propellerhead propensities of the company's dominant engineering culture.

Googlenomics actually comes in two flavors: macro and micro. The macroeconomic side involves some of the company's seemingly altruistic behavior, which often baffles observers. Why does Google give away products like its browser, its apps, and the Android operating system for mobile phones? Anything that increases Internet use ultimately enriches Google, Varian says. And since using the Web without using Google is like dining at In-N-Out without ordering a hamburger, more eyeballs on the Web lead inexorably to more ad sales for Google.

The microeconomics of Google is more complicated. Selling ads doesn't generate only profits; it also generates torrents of data about users' tastes and habits, data that Google then sifts and processes in order to predict future consumer behavior, find ways to improve its products, and sell more ads. This is the heart and soul of Googlenomics. It's a system of constant self-analysis: a data-fueled feedback loop that defines not only Google's future but the future of anyone who does business online.

What Are the Odds?

I don’t think complex situations like this one can be predicted. There are too many uncontrollable or unmeasurable factors. Afterwards, of course, it will appear that some people had gotten it just right: since there are many people making many predictions, no doubt some of them will get it right, if only by chance. But that doesn’t mean that, if not for some unforeseen random turn, things wouldn’t have gone the other way.

The social historian (and socialist) Richard Henry Tawney, wrote, “Historians give an appearance of inevitability… by dragging into prominence the forces which have triumphed and thrusting into the background those which they have swallowed up.” And the (neo)conservative historian Albert Wohlstetter said it this way: “After the event, of course, a signal is always crystal clear. We can now see what event the disaster was signaling … but before the event it is obscure and pregnant with conflicting meanings.”

In some sense this idea is encapsulated in the cliché that “hindsight is always 20/20,” but people often behave as if the adage weren’t true. In government, for example, a “should-have-known-it” blame game is played after every tragedy. In the case of Pearl Harbor, for example, seven committees of the United States Congress delved into discovering why the American military had missed all the “signs” of a coming attack. One of the pieces of evidence cited as a harbinger recklessly ignored by the U.S. Navy was a request, intercepted and sent to the Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington, that a Japanese agent in Honolulu divide Pearl Harbor into five areas and make future reports on ships in harbor with reference to those areas. Of special interest were battleships, destroyers and carriers, as well as information regarding the anchoring of more than one ship at a single dock. In hindsight , that sounds ominous, but at other times similar requests had gone to Japanese agents in Panama, Vancouver, Portland and San Francisco. [The analysis is most famously laid out in the 1963 book, “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision,” by Roberta Wohlstetter, who was married to Albert, noted above.]

In addition to the intelligence reports that in hindsight seem to point toward a specific attack, there is also a huge background of useless intelligence, each week bringing new reams of sometimes alarming or mysterious messages and transcripts that would later prove misleading or insignificant. In advance of the event, you can’t tell one sort from the other.

It is hard to say whether people are too optimistic or too pessimistic. That depends on the person. But we should keep in mind that it is easy to concoct stories explaining the past, or to become confident about dubious scenarios of the future. We should view both explanations and prophecies with skepticism.Can a full understanding of the probability of certain outcomes help reduce anxiety? For instance: would knowing the statistical frequency (or infrequency) of plane crashes help someone overcome a fear of flying? Would a smoker knowing the actual odds that he will get cancer make him less fearful of that outcome? In short, do we worry too much, or too little?

My mother worries too much. Some say I worry too little. I guess that shows a) that one cannot say “we” worry too much or too little, and b) that whether an individual worries too much or too little is not 100 percent inherited from your mother.

I was once on a plane that experienced so much turbulence that when I looked out the window, the wings seemed to flap up and down like a bird’s. I noticed, also, that the woman in the window seat next to me looked pale and terrified. Personally, I took comfort in knowing how many miles planes fly through heavy turbulence without any problems at all. So I explained to the woman how planes were designed to withstand such conditions, and told her the slim odds of anything bad happening. When I finished, she turned away and reached for the barf bag.

Some people take solace in an understanding of their environment, others don’t. For me, an understanding of the role played by chance has taught me that one important factor in success is under our control: the number of at-bats, the number of chances taken, the number of opportunities seized. As someone who has taken risks in life I find it a comfort to know that even a coin weighted toward failure will sometimes land on success. Or, as I.B.M. pioneer Thomas Watson said, “If you want to succeed, double your failure rate.”Wednesday, May 13, 2009

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

Saturday, May 9, 2009

Wednesday, May 6, 2009

Tuesday, May 5, 2009

Saturday, May 2, 2009

One on One with Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman Berkshire Hathaway

GHARIB: How are Berkshire's businesses doing so far this year?

MUNGER: Mixed. But the two biggest businesses, which are insurance and utilities, are flourishing. So I would say that even with all of the bad effects we've had, we're not catching our full share of the horror.

GHARIB: Some of Berkshire's investments are in financial stocks like American Express and Wells Fargo. Does it make sense to continue to hold on to these stocks? What's your outlook for the financials?

MUNGER: Well, I think the companies which we are invested have very respectable futures from this point forward. The financial world should be restructured so that these people who are too big to fail are not allowed to behave in such a gamey fashion. I'm pessimistic with the regulatory changes that come down. I'm afraid they won't be as severe as we need.

GHARIB: As an investment, investors should stay away from financials for now?

MUNGER: I didn't say that. We need the financials. We can't have a modern civilization without strong financial companies. But we don't need them as swashbuckling and as crazy and as venal as they've been.

GHARIB: Now I understand there are three candidates who are being considered to take over from Warren Buffett when the time comes. I know you're not going to tell me who they are. But what do you think is the most important characteristic for this job?

MUNGER: I don't think there's any one way that's the right way to run a corporation. Different people have different styles. Different people have different strengths. I am quite confident that Berkshire will be governed very well long after Warren and I are gone.

Thanks to Sanjeev Parsad from Corner of Berkshire and Fairfax for the original reference

Other Related Articles

Here's the Story on Berkshire's Munger

Buffett's Partner Charlie Munger Blames Banks' "Evil and Folly" For Economic Crisis

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Warren Buffett on Wells Fargo

Fortune: How is Wells Fargo unique?

Warren Buffett: It's sort of hard to imagine a business that large being unique. You'd think they'd need to be like any other bank by the time they got to that size. Those guys have gone their own way. That doesn't mean that everything they've done has been right. But they've never felt compelled to do anything because other banks were doing it, and that's how banks get in trouble, when they say, "Everybody else is doing it, why shouldn't I?"

What about all the smart analysts who think no big bank can survive in its present form, including Wells Fargo?

Almost 20 years ago they were saying the same thing. In the end banking is a very good business unless you do dumb things. You get your money extraordinarily cheap and you don't have to do dumb things. But periodically banks do it, and they do it as a flock, like international loans in the 80s. You don't have to be a rocket scientist when your raw material cost is less than 1-1/2%. So I know that you can have a model that works fine and Wells has come closer to doing that right than any other big bank by some margin. They get their money cheaper than anybody else. We're the low-cost producer at Geico in auto insurance among big companies. And when you're the low-cost producer - whether it's copper, or in banking - it's huge.

Then on top of that, they're smart on the asset size. They stayed out of most of the big trouble areas. Now, even if you're getting 20% down payments on houses, if the other guy did enough dumb things, the house prices can fall to where you get hurt some. But they were not out there doing option ARMs and all these crazy things. They're going to have plenty of credit losses. But they will have, after a couple of quarters of getting Wachovia the way want it, $40 billion of pre-provision income.

And they do not have all kinds of time bombs around. Wells will lose some money. There's no question about that. And they'll lose more than the normal amount of money. Now, if they were getting their money at a percentage point higher, that would be $10 billion of difference there. But they've got the secret to both growth, low-cost deposits and a lot of ancillary income coming in from their customer base.

So what is your metric for valuing a bank?

It's earnings on assets, as long as they're being achieved in a conservative way. But you can't say earnings on assets, because you'll get some guy who's taking all kinds of risks and will look terrific for a while. And you can have off-balance sheet stuff that contributes to earnings but doesn't show up in the assets denominator. So it has to be an intelligent view of the quality of the earnings on assets as well as the quantity of the earnings on assets. But if you're doing it in a sound way, that's what I look at.

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

Valuing Equities in an Economic Crisis or How I Learned to Stop Worrying about the Economy and Love the Stock Market

In their recent panic, investors have driven U.S. equity valuations down below fair value for the first time in well over a decade. This is not particularly surprising given the economic environment, but we should not confuse a predictable event with a justifiable one. Given that we are in an economic crisis, investors were apt to overreact to the bad news and drive the market down, but we believe that this is not warranted given the underlying fundamentals of the market.

John Templeton’s famous line, “The four most dangerous words in investing are ‘This time it’s different,’” is usually taken to apply to New Era bull markets. But it is just as applicable in a bear market. Because the economy is a mean reverting system, things have never been as good as they appeared in the booms, and have never yet been as bad as they appeared in the busts. We believe that this time will not be different, and history, at least, is on our side.

Given our assumptions, fair value for the S&P 500 is around 900. Long-term investors in stocks should therefore do well if they invest at current levels. An investor who correctly guesses that the market will bottom at 600 and waits until then to invest will do even better. But that investor is taking the risk that investors overreact less to this crisis than they have in previous crises and, in waiting for the perfect entry point, may miss the best opportunity to buy equities in over 20 years.

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Warren Buffett takes charge

In acquiring a stake in BYD, Buffett broke a couple of his own rules. "I don't know a thing about cellphones or batteries," he admits. "And I don't know how cars work." But, he adds, "Charlie Munger and Dave Sokol are smart guys, and they do understand it. And there's no question that what's been accomplished since 1995 at BYD is extraordinary."

"How did BYD get so far ahead?" Warren Buffett asked Wang, speaking through a translator. "Our company is built on technological know-how," Wang answered. Wary as always of a technology play, Buffett asked how BYD would sustain its lead. "We'll never, never rest," Wang replied.

Saturday, April 4, 2009

The News Which Never Made the Front Pages

Now, these distractions are not necessarily bad news because it means that news which would normally hit the front pages won’t always get the attention it deserves which, in the world of finance, can only be regarded as an opportunity. And that is precisely what this month’s Absolute Return Letter is about – events which have happened over the past few weeks which didn’t get the attention they deserved.

Fireside Chat -- Martin Capital Management

We can’t call markets, but we can observe human behavior. We suspect that this secular bear market will end with a whimper and not a bang. Futile attempts to pinpoint some elusive bottom will eventually give way to despair. When buying bargains on the sale rack yields nothing but disappointment, when patience wears thin, and when hope is finally abandoned, opportunity

clothed in black will be abundant. While nobody knows to what levels the popular indices might sink—and when—like the flipside of the bull market just passed, one need only be generally right to sleep peacefully at night and earn low-risk, wealth-building rates of return.

Thursday, March 12, 2009

Reinvesting When Terrified

has been so hard to raise in this market of unprecedented illiquidity. As this crisis climaxes, formerly reasonable people will start to predict the end of the world, armed with plenty of terrifying and accurate data that will serve to reinforce the wisdom of your caution. Every decline will enhance the beauty of cash until, as some of us experienced in 1974, ‘terminal paralysis’ sets in. Those who were over invested will be catatonic and just sit and pray. Those few who look brilliant, oozing cash, will not want to easily give up their brilliance. So almost everyone is watching and waiting with their inertia beginning to set like concrete. Typically, those with a lot of cash will miss a very large chunk of the market recovery.

For the record, we now believe the S&P is worth 900 at fair value or 30% above today’s price. Global equities are even cheaper.

In June 1933, long before all the banks had failed or unemployment had peaked, the S&P rallied 105% in 6 months. Similarly, in 1974 it rallied 148% in 5 months in the UK! How would you have felt then with your large and beloved cash reserves? Finally, be aware that the market does not turn when it sees light at the end of the tunnel. It turns when all looks black, but just a subtle shade less black than the day before.

Tuesday, March 10, 2009

Friday, March 6, 2009

Sunday, March 1, 2009

Saturday, February 28, 2009

Insight: The flight of the long run

If the long-run expected return on bonds in the future were higher than the expected return on equities, the capitalist system would grind to a halt, because the reward system would be completely out of whack with the risks involved. After all, from the end of 1949 to the end of 2000, the S&P 500 provided a total annual return of 13.1 per cent, while long Treasuries could grind out only 5.8 per cent a year.

But does this history really tell us anything about what lies ahead? Neither the awesome historical track record of equities nor the theoretical case is a promise of a realised equity risk premium. John Maynard Keynes, in an immortal observation about the future, expressed the matter in simple but obvious terms: “We simply do not know.”

Will our economy and society emerge so risk-averse after these experiences that years will have to pass before we return to a system naturally generating vibrant economic growth and a renewed willingness to both borrow and lend? Or will we head in the opposite direction, where faith in ultimate bail-outs will justify the wildest kind of risk-taking? Or will the entire structure collapse from government debts and deficits that turn out to be so unmanageable that chaos is the ultimate result?

We can neither answer those questions nor can we claim they are a complete list of the possibilities. The unknown today seems more than usually unknown. Then my whole point remains the same. The long run is an impenetrable mystery. It always has been.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Interview With RAY DALIO, Bridgewater Associates ( + his Annual Letter to Clients )

Barron's: I can't think of anyone who was earlier in describing the deleveraging and deflationary process that has been happening around the world.

Dalio: Let's call it a "D-process," which is different than a recession, and the only reason that people really don't understand this process is because it happens rarely. Everybody should, at this point, try to understand the depression process by reading about the Great Depression or the Latin American debt crisis or the Japanese experience so that it becomes part of their frame of reference. Most people didn't live through any of those experiences, and what they have gotten used to is the recession dynamic, and so they are quick to presume the recession dynamic. It is very clear to me that we are in a D-process.

I guess I'm thinking of the examples of people and businesses with solid credit records who can't get banks to lend to them.

Those examples exist, but they aren't, by and large, the big picture. There are too many nonviable entities. Big pieces of the economy have to become somehow more viable. This isn't primarily about a lack of liquidity. There are certainly elements of that, but this is basically a structural issue. The '30s were very similar to this.

By the way, in the bear market from 1929 to the bottom, stocks declined 89%, with six rallies of returns of more than 20% -- and most of them produced renewed optimism. But what happened was that the economy continued to weaken with the debt problem. The Hoover administration had the equivalent of today's TARP [Troubled Asset Relief Program] in the Reconstruction Finance Corp. The stimulus program and tax cuts created more spending, and the budget deficit increased.

At the same time, countries around the world encountered a similar kind of thing. England went through then exactly what it is going through now. Just as now, countries couldn't get dollars because of the slowdown in exports, and there was a dollar shortage, as there is now. Efforts were directed at rekindling lending. But they did not rekindle lending. Eventually there were a lot of bankruptcies, which extinguished debt.

In the U.S., a Democratic administration replaced a Republican one and there was a major devaluation and reflation that marked the bottom of the Depression in March 1933.

What about bonds? The conventional wisdom has it that bonds are the most overbought and most dangerous asset class right now.

Everything is timing. You print a lot of money, and then you have currency devaluation. The currency devaluation happens before bonds fall. Not much in the way of inflation is produced, because what you are doing actually is negating deflation. So, the first wave of currency depreciation will be very much like England in 1992, with its currency realignment, or the United States during the Great Depression, when they printed money and devalued the dollar a lot. Gold went up a whole lot and the bond market had a hiccup, and then long-term rates continued to decline because people still needed safety and liquidity. While the dollar is bad, it doesn't mean necessarily that the bond market is bad.

I can easily imagine at some point I'm going to hate bonds and want to be short bonds, but, for now, a portfolio that is a mixture of Treasury bonds and gold is going to be a very good portfolio, because I imagine gold could go up a whole lot and Treasury bonds won't go down a whole lot, at first.

Ideally, creditor countries that don't have dollar-debt problems are the place you want to be, like Japan. The Japanese economy will do horribly, too, but they don't have the problems that we have -- and they have surpluses. They can pull in their assets from abroad, which will support their currency, because they will want to become defensive. Other currencies will decline in relationship to the yen and in relationship to gold.

Bridgewater Associates Annual Letter to Clients

Friday, January 23, 2009

GMO QUARTERLY LETTER ( + A Recent Interview by Forbes.com )

Slowly and carefully invest your cash reserves into global equities, preferring high quality U.S. blue chips and emerging market equities. Imputed 7-year returns are moderately above normal and much above the average of the last 15 years. But be prepared for a decline to new lows this year or next, for that would be the most likely historical pattern, as markets love to overcorrect on the downside after major bubbles. 600 or below on the S&P 500 would be a more typical low than the 750 we reached for one day.

In fixed income, risk finally seems to be attractively priced, in that most risk spreads seem attractively wide. Long government bond rates, though, seem much too low. They reflect the short-term fears of economic weakness and the need for low short-term rates. We would be short long government bonds in appropriate accounts.

As for commodities, who knows? There were a few months where they looked like a high-confidence short, but now they are half-price or less, and are much lowerconfidence bets.

In currencies, we know even less. It is easy to find currencies to dislike, and hard to find ones to like. There are no high-confidence bets, in our opinion. For the long term, research should be directed into portfolios that would resist both inflationary problems and potential dollar weakness. These are the two serious problems that we may have to face as a consequence of flooding the global financial system with government bailouts and government debt.

Fearless Forecasts for the Long Term

Under the shock of massive deleveraging caused by the equally massive write-down of perceived global wealth, we expect the growth rate of GDP for the whole developed world to continue the slowing trend of the last 12 years as we outlined in April 2008. Since this recent shock overlaps with slowing population growth, it will soon be widely recognized that 2% real growth would be a realistic target for the G7, even after we recover from the current negative growth period. Emerging countries are, of course, a different story. They will probably recover more quickly, and will continue to grow at double (or better) the growth rate of developed countries. (See “The Emerging Emerging Bubble,” April 2008.)

Warren Buffett "Not Opposed" to Berkshire Hathaway Stock Buyback: The Complete PBS Interview Transcript

BUFFETT: (Laughs.) I wouldn’t name a number. If I ever name a number, I’ll name it publicly. I mean, if we ever get to the point where we’re contemplating doing it, I would make a public announcement.

GHARIB: But would you ever be interested, are you in favor of buying back shares?

BUFFETT: I think if your stock is undervalued, significantly undervalued, that a management should look at that as an alternative to every other activity. That used to be the way people bought back stocks, but in recent years, companies have bought back stocks at high prices. They’ve done it because they like supporting the stock. They don't ever say it.

GHARIB: In your case, with Berkshire. I mean, it's down a lot. It was up to 147-thousand last year. Would you ever be opposed to buying back stock?

BUFFETT: I’m not opposed to buying back stock.

Thursday, January 22, 2009

Long-Term Investing: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Ignore Volatility

• First, I’d like to define what I think risk means. The central point is that how you define risk has a lot to do with your time horizon.

• Second, I’ll discuss how you can help avoid catastrophe. Common to all great long-term investment track records is the managers survived in all kinds of environments.

• Finally, I touch on some behavioral issues—or why dealing with the long-term in the face of volatility is emotionally, physically, and psychologically hard. I’ll wrap up with some suggestions on what you can do if you accept my perspectives.

OK. If you have bought in to my comments on risk, catastrophe, and psychology, what should you consider doing?

1. Decide if you can be or should be a long-term investor. There’s nothing sacred about it—you just have to make sure you properly align your thinking, policies, and processes around your time horizon.

2. Don’t overbet. Constantly consider the problem of induction and the deleterious effects of leverage and incentives.

3. Work to reduce stress and maintain perspective. Some documented ways to lower stress include:

a. Exercise

b. Maintain and cultivate social connections (family & friends)

c. Get sleep and maintain a healthy diet

4. Don’t dwell on short-term portfolio moves. Sidestep loss aversion if possible.

5. Remember the story from Abraham Lincoln. He recounted that an Eastern monarch once charged his wise men to invent him a sentence that would be true in all situations. They came back with the words: “And this, too, shall pass away.” As Lincoln said, this phrase “chastens in the hour of pride, and consoles in the depths of affliction.” This too shall pass and long-term investors stand well to gain. 12

Monday, January 19, 2009

Warren Buffett's Dateline Interview with NBC's Tom Brokaw: The Complete Transcript

I've been describing this as the domestic equivalent of war. Is that an overstatement?

BUFFETT:

Well, actually, in September I said-- this is an economic Pearl Harbor. I-- that was the time congress had made it in. It really is an economic Pearl Harbor. It-- the-- the country is facing something it hasn't faced since World War II.

And they're fearful about it. And they don't know quite what to do about it. And the point is-- and-- and it-- and temporarily it looks like we're losing. It has that-- that same aspect. Interestingly enough, we were losing for a while after Pearl Harbor. But the American people never doubted that we'd win. I mean, we had that attitude then. I think, right now, that they're sort of paralyzed.

BROKAW:

And how long will it be before Warren Buffet is tooling around Omaha in an electric car?

BUFFETT:

Well, we have this investment -- (LAUGHTER) in a Chinese company. I'm going to have-- I'm going to have an electric car at the annual meeting at Berkshire next year.

BROKAW:

And is that gonna be the future of this country as well?

BUFFETT:

Well, I-- I think an electric car is-- is definitely part of the future. I mean I-- it-- it makes so much sense. I mean, the battery, obviously, is the big stumbling block. But we-- we'll figure out how to do that. I mean, we figured out a lot of things in this-- I-- I will predict that within-- certainly within five years, there is a-- a reasonably priced electric car that will go a long way with a plug in arrangement.

BROKAW:

Paul Krugman, among others, says we're not doing enough. That we've got to even-- open the valves even greater than we have been. A lot of people are concerned about the deficit and what the consequences are gonna be down the stream. Are we doing enough?

BUFFETT:

I don't know the perfect answer. Nobody else does either. I mean, Paul Krugman doesn't know it. And Barack Obama doesn't know it. And (Treasury Secretary-Designate) Tim Geithner doesn't know it. All we know is we have to do something on a very major scale. And if we find out six months down the road that we've-- you know, we've gone a little off course, left of right, we-- that can be adjustment-- we do not want to sit around and debate for six months what the perfect solution is.

We wouldn't know it if we found it. The-- the Morton thing to do is do what we know we need to do now. And-- and we'll always-- there will always be critics on that. That-- that-- the important thing is, that the person that's there takes the action that makes sense at the time. Did we handle the-- the aftermath of Pearl Harbor the next month perfectly? I don't know whether we did or not. But I would doubt that. You know, somebody now can come up with a better system. The important thing is, we got going.

Friday, January 16, 2009

Hoisington Quarterly Review and Outlook -- THE GREAT EXPERIMENT

While the historical record indicates that the ultimate low in Treasury yields lies years away, the path to the ultimate low will be anything but smooth or linear as significant volatility continues. As the experience from U.S. and Japanese history indicates, many “false dawns” will occur, with investors assuming that the long-delayed cyclical recovery in economic activity is at hand. During these pleasant but relatively short interludes, stock prices will probably rise dramatically and bond yields will increase. If history is a guide, however, these episodes will further drain wealth and will be thwarted by the persistent forces of the debt deflation. With yields in the long Treasury market very low in nominal terms, the real return will be greater if deflation sets in. Moreover, in Japan from 1988 to the present, as well as in the U.S. from 1872 to 1892 and 1928 to 1948, the total return on Treasury bonds exceeded the total return on stocks. Such a condition cannot happen for the long run, but it did happen in these three instances spanning two decades. As a hedge against a recurrence of a prolonged debt deflation, some investors may want to consider even larger positions in high quality, long term Treasury securities.

Biggest meltdown winner: be very wary

The crux of the problem

“De-leveraging” is hoarding, paying down debt, postponing expenditures by banks, individuals and companies which is contributing to the recession and deflation of prices, he explained.

The two historical examples of the serious meltdown the world now faces occurred in the 1930s after the 1929 market crash and Japan’s economic malaise since its 1989 meltdown, not as severe but nonetheless serious.

“In the case of both those data points, the de-leveraging was so severe that even though governments built infrastructure and interest rates went to zero the economy did not around,” he said.

“De-leveraging means that the value of houses, for instance, have to go down so low that people will start to turn around to buy them again. It means that factories with excess capacity will have to close until demand returns and makes surviving factories busy again,” he said. “It might take four or five years.”

Political vigilance is critical

The danger signs are if any of the three disastrous policies from the 1930s rear their ugly heads again: tariff barriers; higher taxes to balance budgets or higher interest rates to support currencies.

“These are the kind of things you have to look for as signals about the future,” he said. “If Obama starts talking about `Buy American’ that’s less obvious but is a form of protectionism that may impede a turnaround.”

Another unintended consequence that may loom is the exchange rate issues such as the concern about China’s low value or that Greece, Ireland and Spain have been downgraded by S&P because they are not meeting Euro standards. Their debts and spending are too high.

“One of those countries may leave the Euro or be booted out,” he said.

Overall optimism

Its most recent deal was Northbridge’s privatization and is an example of Fairfax’s financial heft. “We took Northbridge public in 2003 because we needed the money. We owned it for 23 years and its now Canada’s biggest commercial lines company,” he said. “It went public at 1.2 times’ book value at C$15 a share. In the fourth quarter we had a US$350 million dividend from a U.S. investment so we made an offer to buy out the rest of Northbridge for 1.3 times’ book value and a 30% premium to its average trading price or C$39 a share.”

Northbridge shareholders, 67% of whom acceded to the deal, made 20% compounded annually if they had held the stock since 2003.

Watsa also owns a chunk of CanWest whose stock has fallen dramatically, but remains a loyal, long-term investor.

Fairfax is optimistic overall, has been carefully investing and took the hedges off its portfolios this fall but remains vigilant. And Watsa believes that allinvestors should do the same.

Tuesday, January 13, 2009

Saturday, January 10, 2009

Bruce Berkowitz: “Prices today are as attractive as I have seen in my career”

This is an excellent question and it goes to the key issues behind our investment. We bought ACF because we believed there was significant value in the company through its ability to generate free cash flow. Then we looked at ways in which we could “kill” the company – i.e., what kinds of mistakes or misfortunes could impair our investment. In the case of ACF, we believe that in some of those scenarios – such as in run-off mode – we could get significantly higher value. The tangible book value should start to approximate the liquidation value. But then we look for what is not included in the tangible value, such as the time value of money (e.g., the present value of future insurance premiums) and whether the tangible values are really

tangible (e.g., whether their fixed assets are fairly valued on their balance

sheet).

In the worst case, we will make some pretty good money.

I look at my Board seat as a way to protect our shareholders’ value. It does not affect my relationships with or ability to invest in any other companies. In fact, it expands my knowledge of related industries, from automobile lending to dealerships to insurance. When the time comes to sell our investment, I will leave the Board. I do not accept any compensation, such as fees or

restricted stock grants. Only my travel expenses are reimbursed. I will only stay on the Board to help our shareholders.

Based on your metric of free cash flow yield, how cheap or expensive is the

overall market on a historical basis?

The last tough environment was in 1987, but that was a sudden shock and not a big event. Within a year the markets had recovered. In the Dot Com era the markets were caught in a mania, but the current crisis is much worse than what occurred at the end of that bubble, which was contained in the tech sector.

You would have to go back to 1974, when even the smartest investors were down 50% or 60%. I cannot say whether the market is as under-valued today as it was then, but certainly we are seeing valuations for companies in our portfolio that are comparable to those of 1974.

What should investors expect from the market in 2009?

I don’t mind tough questions but this is an impossible question. There are two ways to invest – either predicting or reacting. I admit I have no skill at predicting. To predict would be foolish, so we react. We invest based on free cash flow relative to the price of a stock. We could be bouncing around the bottom of the market. But I don’t know whether the true bottom will come in 31 days or 31 months. Prices today are as attractive as I have seen in my career and it will be worth the wait for the market to deliver the true value of these companies.